The Medicare Cost Shift: Myth, Math, and a Fix That Works

Employers Must Stop Being ATMs for Hospital Systems

There’s a persistent health policy yarn that just refuses to die: the idea that employers – via their commercial insurance plans – are forced to substantially subsidize shortfalls from Medicare, Medicaid, and charity care. The narrative goes like this: hospitals lose money on government payers, so they jack up private insurance rates to make up the difference. Presto, the “cost shift.” It’s a tidy, linear tale. But dig a little deeper, and the story starts to fray.

I know because this oversimplification has victimized me in the past. Let’s get one thing straight up front: the cost shift isn’t pure fiction. But it sure isn’t gospel truth, either. The actual magnitude of this shift varies tremendously, whether we’re talking about Medicare (for our seniors) or Medicaid for the impoverished.

Is the Cost Shift Real?

On the surface, the hospital industry’s case for a cost shift seems compelling. According to the American Hospital Association, Medicare paid hospitals only 82 cents for every dollar they spent treating Medicare patients in 2022 (Infographic: Medicare Significantly Underpays Hospitals for Cost of Patient Care | AHA) – translating to $99.2 billion in underpayments that year (Infographic: Medicare Significantly Underpays Hospitals for Cost of Patient Care | AHA). No wonder hospitals cry foul. Meanwhile, private health plans often pay two to three times the Medicare rate for the exact same services. In fact, a new RAND analysis found that in 2022, employers and private insurers paid on average 254% of what Medicare would have paid for hospital care (Private Health Plans During 2022 Paid Hospitals 254 Percent of What Medicare Would Pay | RAND). Some states’ averages are even higher, topping 300% of Medicare (Private Health Plans During 2022 Paid Hospitals 254 Percent of What Medicare Would Pay | RAND). So the logic appears straightforward: squeeze the employers and their insurers to offset what the government doesn’t pay.

But here’s the twist – empirical evidence doesn’t totally back it up. Multiple studies over the years have found that hospitals typically recoup only a fraction of each dollar cut from Medicare through higher private prices. One rigorous analysis of past payment shifts found private prices rose only about $0.21 for each $1 drop in public payments (A Cost Shift Study Done Right | The Incidental Economist). Another study out of Yale pegged it at just $0.17 per dollar (Cooper et al., 2018). Even at the high end, a comprehensive review by economist Austin Frakt concluded the shift was on the order of $0.21 to $0.33 on the dollar – nowhere close to a full make-up. (Frakt, A. B. (2011). How Much Do Hospitals Cost Shift? A Review of the Evidence. The Milbank Quarterly, 89(1), 90–130). In plain English, cost shifting happens, but it’s modest, not dollar-for-dollar.

Real-world experiments bear this out. The Colorado Health Institute looked at what happened after Colorado expanded Medicaid in the 2010s. If the cost shift theory were airtight, one would expect that giving hospitals more Medicaid revenue (and reducing their uncompensated care) would lead to lower prices for privately insured patients. What actually happened? Commercial insurance premiums kept climbing regardless (The Cost Shift Myth | Colorado Health Institute). A state report found that Medicaid expansion did not lead to more affordable private insurance, and hospital prices continued to rise despite the infusion of public dollars (The Cost Shift Myth | Colorado Health Institute). In short, when hospitals got paid more by government programs, they didn’t dial back what they charged private plans.

The data is messy and nuanced, but the takeaway is this: cost shifting exists, but it’s neither linear nor deterministic. Hospitals don’t automatically charge $1 more to private payers for each $1 Medicare doesn’t pay. The far bigger factor in what hospitals charge private insurers? Market power. A consolidated hospital system with dominant market share will charge high prices because it can – not strictly because it’s compensating for Medicare or Medicaid (The Cost Shift Myth | Colorado Health Institute) (Private Health Plans During 2022 Paid Hospitals 254 Percent of What Medicare Would Pay | RAND). In markets where a hospital faces little competition, it has free rein to demand 250% or 300% of Medicare from commercial health plans, cost shift narrative or not. In competitive markets, by contrast, hospitals have less leverage to hike prices. As the RAND researchers noted, very little of the variation in hospital prices can be explained by a hospital’s share of Medicare/Medicaid patients – prices vary primarily due to hospitals’ negotiating clout, not their payer mix (Private Health Plans During 2022 Paid Hospitals 254 Percent of What Medicare Would Pay | RAND).

Can Hospitals Turn a Profit on Medicare?

This is where the hospital sob stories begin to crack. The AHA often frames Medicare as a guaranteed money-loser, citing figures like an average -12.7% Medicare margin in 2022 (i.e. a double-digit loss) in its lobbying and PR. But let’s not confuse averages with absolutes. Not every hospital is hemorrhaging money on Medicare patients – far from it.

Take North Carolina as a case in point. The North Carolina State Health Plan (the employee health plan for state workers) teamed up with researchers to dig into actual hospital financial filings. They found that from 2015 to 2020, the majority of hospitals in NC made money on Medicare. In 2020 alone, while hospital lobbyists were publicly claiming a $3.1 billion Medicare shortfall, the hospitals’ own cost reports showed a net $87 million profit on Medicare statewide (North Carolina Hospitals Profit on Medicare | NC State Health Plan). You read that right: in aggregate, NC hospitals were in the black on Medicare, despite their complaints of massive losses. One striking example: Atrium Health (a large NC system) had loudly claimed a $640 million loss on Medicare patients. But when you include Medicare Advantage (private Medicare plan) payments, Atrium actually cleared a $119 million profit on Medicare in the same year (North Carolina Hospitals Profit on Medicare | NC State Health Plan). It’s not exactly fraud – but it sure is creative accounting and selective storytelling. Hospitals often count only traditional Medicare and exclude the often-higher payments from Medicare Advantage to pad their “loss” figures. When all Medicare dollars are counted, the picture isn’t nearly as dire as the industry paints.

This isn’t unique to one state, either. Federal analysts at the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) have for years noted that some hospitals – generally those run most efficiently – can break even or even post small profits on Medicare rates. In prior reports, MedPAC identified a subset of hospitals that consistently delivered high-quality care at lower costs; these “relatively efficient” hospitals were able to achieve modest positive Medicare margins (+2% to +3%) in some years (MedPAC's March 2014 Report to Congress). They’re outliers, but they prove it’s possible. These are typically hospitals that don’t splurge on fancy new buildings or excess administrative layers – they run lean and focus on core mission and efficiency.

So yes, on average Medicare pays less than cost, and many hospitals do lose money on Medicare patients. But that’s not because Medicare rates are inherently unsustainable; it’s often because hospitals have built cost structures around the plush margins of private insurance. They’re accustomed to getting paid 250% of Medicare by commercial plans and have grown expenses (and expectations) accordingly. When you’re addicted to 300% of Medicare from private payers, getting 100% (or 82%, in AHA’s telling) from Medicare feels like an insult. But a more efficient hospital – or one that isn’t using private insurance like an ATM – can live with Medicare rates. And many already do.

How Much Efficiency Does It Take?

Not as much as you’d think. Let’s run a very simple example: Say a hospital currently spends $100 per patient. Medicare reimburses it $82. That’s an $18 shortfall on that patient. The conventional wisdom is the hospital will then charge private insurers $118 or more to make up the difference. But what if, instead, the hospital tightened its belt – trimmed some fat from that $100 cost? Perhaps through leaner staffing (reducing unnecessary admin roles and expensive executives), smarter supply purchasing, and cutting back on luxury perks, the hospital brings its average cost down to $80 per patient. Now Medicare’s $82 payment actually leaves the hospital $2 in profit on that patient. Surprising? It shouldn’t be. Operate efficiently, and Medicare doesn’t have to be a money pit – it can even be marginally profitable.

A $2 per patient profit may sound trivial, but multiply that across tens of thousands of Medicare discharges, and it becomes real money. The point is that unlike private plans (which often pay hospitals exorbitant markups that cover any amount of waste), Medicare forces a degree of fiscal discipline. For hospitals willing to operate efficiently, Medicare can be survivable – even sustainable.

This isn’t just theory. Hospitals that prioritize efficiency, eliminate bloat, and avoid gold-plating their facilities can and do succeed on Medicare rates. They may be rare, but they’re not unicorns. They’re hospitals that focus on their mission rather than building empires. In fact, industry research suggests many hospitals have substantial room to improve. One study found that hospitals which managed to significantly improve their profit margins did so largely by reining in costs on a per-bed basis – the difference between hospitals that improved margins and those that didn’t was over $113,000 per bed per year in adjusted revenues and expenses ( Factors of U.S. Hospitals Associated with Improved Profit Margins: An Observational Study - PMC ). That illustrates just how much potential savings (or extra revenue padding) might exist on a per-bed basis. And a Harvard Business Review analysis laid out concrete steps hospitals could take to get there. The authors outlined five strategies to shrink the Medicare shortfall without any increase in rates: invest in data analytics to find efficiency opportunities, streamline corporate overhead (and outsource non-core functions where sensible), tighten up purchasing of medical supplies and technology (ensure new equipment is evidence-based and not just physician preference), standardize clinical protocols for care to reduce costly variation, and enforce physician adherence to those protocols (5 ways hospitals can mitigate Medicare losses - Becker's Hospital Review | Healthcare News & Analysis) (5 ways hospitals can mitigate Medicare losses - Becker's Hospital Review | Healthcare News & Analysis). In short, use better management instead of simply demanding more money.

Even rural hospitals, often portrayed as the most vulnerable, can find sustainability with modest changes. Yes, rural facilities have lower patient volumes, which makes finances challenging. But they also tend to have smaller scale and often lower labor costs than big urban hospitals. Analyses have suggested that many rural hospitals could stabilize their finances with single-digit percentage reductions in operating costs – on the order of 5–10%. A little more diligence in expense management, a little less overbuilding, and more realistic payment arrangements can keep rural providers solvent without leaning on extortionate private insurance rates. In other words, it doesn’t take a miracle for hospitals to live within the means of reasonable reimbursements. It takes focus and willingness to shed the “charge whatever we want” mentality.

The Fix: Pay 120% of Costs or 125% of Medicare (Whichever Is Higher)

So, what’s a fair, transparent way to pay hospitals that encourages efficiency but also keeps them in business? Here’s one idea: Reference-Based Pricing (RBP) anchored to the greater of a fixed percent of hospital costs or a fixed percent of Medicare. In practice, for example, an employer health plan could decide it will pay the higher of 120% of a hospital’s reported costs or 125% of the Medicare rate for the service. This kind of model puts a reasonable limit on what hospitals can charge, while still ensuring they come out ahead on each patient.

Let’s see how this would work in real numbers:

Scenario 1: An average hospital. Suppose a hospital’s internal cost to perform a procedure is $100. Medicare would pay them $82 for that procedure. Under our RBP model, we calculate 120% of cost = $120, and 125% of Medicare = $102.50. The rule is we pay the higher of the two, which in this case is $120. The hospital gets $120 on a cost of $100 – a $20 profit (20% margin) on that case. Not too shabby.

Scenario 2: A highly efficient hospital or one in a high-cost Medicare area. Say this hospital’s cost is still $100, but because it’s very efficient (or in an area where Medicare rates are adjusted higher), Medicare pays $112 for the procedure. Now 120% of cost is still $120, but 125% of Medicare is $140. The higher amount is $140, so that’s what the hospital gets. That yields a $40 profit per case – double the margin it would have earned under the cost-based formula alone. In other words, if a hospital already runs efficiently or has relatively generous Medicare rates due to regional factors, it can actually earn more under the Medicare-based benchmark. This rewards hospitals that keep costs down.

Scenario 3: A higher-cost hospital, e.g. a rural facility. Suppose a small rural hospital has a cost of $200 for a procedure, and Medicare pays $164. Under RBP, 120% of cost is $240, and 125% of Medicare is $205. Here 120% of cost ($240) is the higher benchmark, so the hospital would get $240 – meaning a $40 profit above its costs. Even a relatively inefficient hospital isn’t left bleeding; it gets a 20% cushion above cost. But notice, in the earlier scenario, a leaner operation in a favorable Medicare market was paid more ($140 on $100 cost, a 40% margin). This two-pronged approach incentivizes efficiency (because efficient hospitals can benefit from the Medicare-based cap) while always ensuring hospitals receive above their full costs.

In all these cases, the hospital makes a profit – $20, $40, etc. It’s not getting rich like it might off a commercial plan today, but it’s certainly not going bankrupt either. RBP structured this way would put a hard ceiling on price gouging while still covering costs, plus a fair margin. Hospitals would have every incentive to streamline operations (since extravagance won’t be paid for), but they would also know that if they truly can’t reduce costs beyond a point, they’ll at least get 120% of whatever their costs are. It’s a balance between fairness and efficiency.

The Gotcha: Gaming the “Cost” – Guardrails Needed

Now, you might be thinking: if we agree to pay based on hospitals’ self-reported costs, won’t hospitals just find ways to make their costs look as high as possible? Bingo. That’s the big caveat. History has shown that when reimbursements were tied to reported costs (like in the old cost-plus days of Medicare), many hospitals responded by inflating their costs. If you give hospitals a blank check of “we’ll pay 120% of whatever you claim your costs are,” you’re practically inviting them to raise that bar.

We’ve seen hints of this kind of “creative accounting” in the current system too. Remember Atrium Health in North Carolina? They claimed a massive $640 million Medicare loss until the fuller picture revealed a $119 million profit once all revenues were counted (North Carolina Hospitals Profit on Medicare | NC State Health Plan). Hospitals know how to allocate and classify costs in ways that can paint a picture of slim margins even when the reality is far rosier. Allowing them to directly set the reimbursement target by simply reporting higher costs would be dangerous without oversight.

So yes, any plan that pegs payment to costs must come with serious guardrails. We can’t have the honor system here. That means independent audits of hospital cost reports – regularly and rigorously. If a hospital is caught inflating costs (tacking executive bonuses, marketing, or fancy new lobbies onto “patient care” costs, for example), there need to be real consequences. Think financial penalties, mandatory repayment of overages with interest, public disclosure of the violations, and even potential loss of tax-exempt status for nonprofit hospitals that egregiously game the system. In other sectors, if you defraud the payer, you face fraud charges; healthcare should be no different.

Additionally, we’d likely need some standardized definitions and regional cost benchmarks. Hospitals shouldn’t be able to label every expense under the sun as “necessary cost” for patient care. Reasonable limits should be placed – e.g., administrative salaries above a certain threshold, lavish facilities, or PR campaigns shouldn’t count as costs that justify higher reimbursement. Maybe we set regional caps: if Hospital X in Chicago says its cost for an appendectomy is $50,000 while every other hospital in Chicago is doing it for $20,000, that should raise a red flag and trigger scrutiny or default to the Medicare-based rate. The goal is to prevent abuse: 120% of “cost” should not become a blank check for inefficiency or profiteering.

With robust enforcement and transparency, however, a cost-based reference price could be a game-changer. It rewards hospitals that manage their resources well (they keep more of the Medicare-indexed payments as profit) and pushes inefficient hospitals to get their act together. Without enforcement, you’re just pouring water into a leaky bucket – hospitals will always claim they need more. With enforcement, you create a blueprint for fair, rational pricing that aligns payment with actual costs of care and a modest margin.

Let’s Call the Bluff on High Hospital Prices

It’s time to dispel the convenient myth that sky-high commercial hospital rates are simply an altruistic subsidy for the underpayments of government programs. The cost shift narrative has been used as a smokescreen. It’s not what’s truly driving private insurance rates through the roof. The real forces are hospital market consolidation, lack of competition, and raw pricing power – aided and abetted by health insurers’ perverse incentives.

Employers – especially those who self-fund their health plans – have effectively been gaslit into believing that paying 250% or 300% of Medicare rates is somehow doing their patriotic duty to keep hospitals afloat. They’ve been told that if they push back on prices, they’ll cripple their local hospitals. That’s bunk. Yes, on average hospitals lose money on Medicare patients, but as we’ve seen, that’s often because those hospitals are addicted to the Cadillac margins from private payers. Medicare’s rates aren’t unreasonable by any objective measure – many hospitals can and do live within them. It’s just that hospitals have gotten used to a system where they can charge whatever the market will bear and then justify it after the fact by pointing at Medicare shortfalls.

Meanwhile, look at the big picture of hospital finances. In the years leading up to the pandemic, U.S. hospitals as a whole were doing quite well. Even including the ups and downs of 2020–2022, hospitals have often posted robust surpluses. Total profits for U.S. hospitals have ranged from tens of billions up to over $100 billion a year in the last decade (Hospital Margins Rebounded in 2023, But Rural Hospitals and Those With High Medicaid Shares Were Struggling More Than Others | KFF). In 2021, for instance – a year buoyed by relief funds – hospitals’ aggregate total margin was about 10.8%, which on roughly $1.3-$1.4 trillion of revenue works out to well over $100 billion in profit.

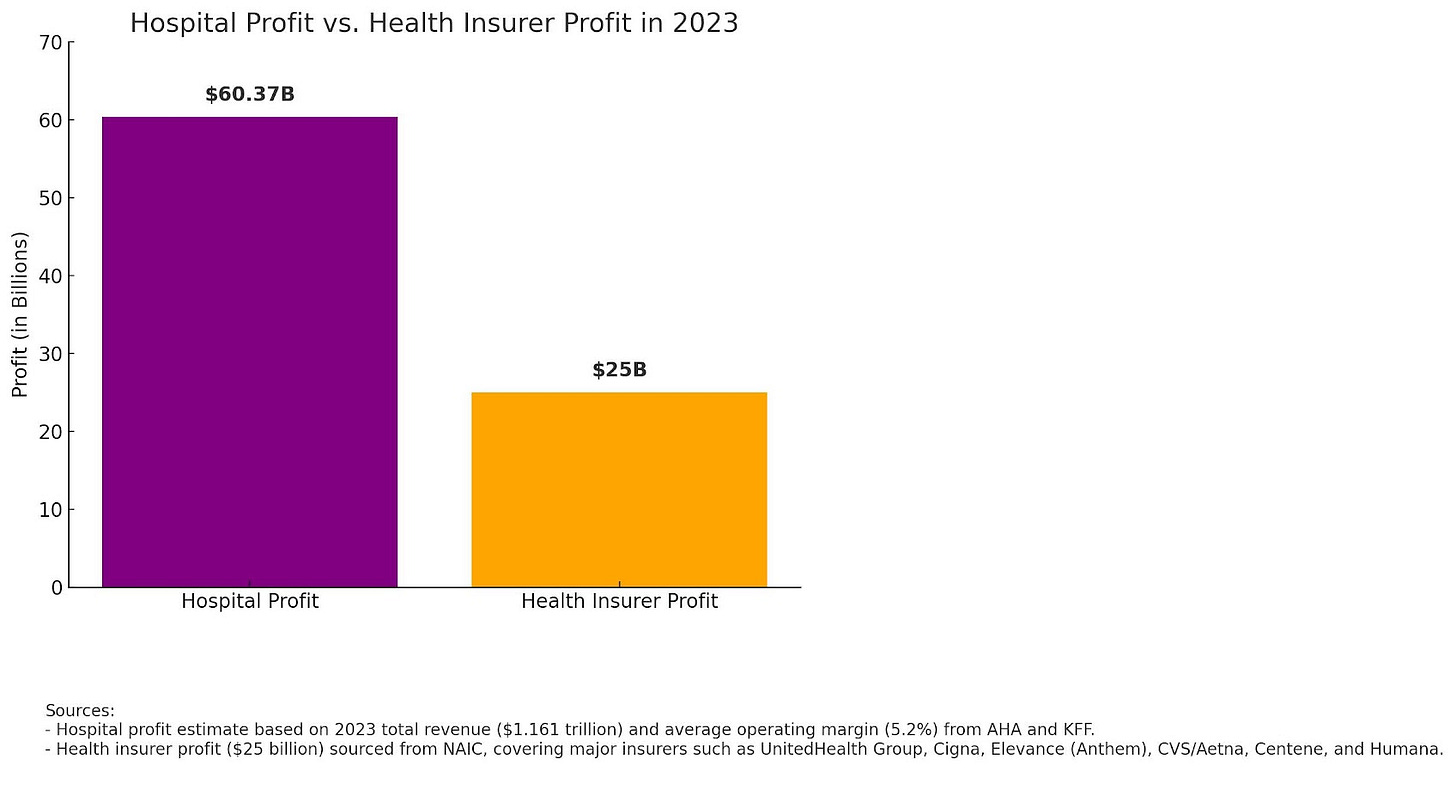

In this outstanding podcast with Stacey Richter and Vivian Ho, Vivian explains that in 2023, hospitals made $125 Billion, while insurers made $25 Billion. I decided to research the topic on my own and came up with the below ($60B for hospitals and $25B for insurers), but that was a back-of-the-napkin estimate. I have little doubt that Vivian’s numbers are more accurate.

Hospitals are not exactly impoverished. Many have sizable financial reserves – cash, investments, even endowments in the case of large nonprofits.

Now compare that with health insurance companies. The entire health insurance sector’s profits, across all insurers, typically sum up to a fraction of hospital industry profits. $25 billion annually – a lot of money, to be sure, but far less than what hospitals net. Margins for insurers run 3-5% on average (Medical Loss Ratio’s Role in the Large Group Insurer Market), whereas hospital operating margins (pre-pandemic) were often 7-8% and total margins even higher (Hospital Margins Rebounded in 2023, But Rural Hospitals and Those With High Medicaid Shares Were Struggling More Than Others | KFF). This isn’t to portray insurers as saints by any means, but it busts the narrative that “greedy insurance companies” are the sole villains. In truth, hospitals have been sitting on a bigger cushion.

So when hospitals blame insurers for high premiums, and insurers blame hospitals’ prices, they’re both right to a degree – but hospitals have had the leverage to command those prices, and they’ve used it liberally. The cost shift story has been a useful political talking point, but it doesn’t justify the routine 250-300% of Medicare price tags employers are paying. The idea that employers must pay that much “or else hospitals go under” simply isn’t supported by the data.

Why Insurers Don’t Fight High Costs

One of the more frustrating, under-discussed truths in this whole saga: traditional insurance carriers have little incentive to aggressively control hospital costs under the current rules. In fact, the Affordable Care Act’s Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) provision arguably rewards insurers when costs go up. It sounds crazy, but here’s how it works.

MLR Price Caps

The ACA’s MLR rules require insurers to spend at least 80-85% of premium dollars on actual medical care (the threshold is 80% for individual/small group plans, 85% for large group) (Medical Loss Ratio | CMS). That means they can keep 15-20% for administration, overhead, and profit. If they spend less than that on medical claims, they actually have to issue rebates to customers to bring their margins back down into the allowed range. The rule was meant as a consumer protection – to cap insurer profits and ensure most of your premium goes to care. And it does prevent egregious profiteering. But it also creates a perverse dynamic: an insurer’s gross profit in dollars can grow if total claims grow, because their cut is a percentage.

Think of it this way: if an insurer is allowed, say, a 15% admin/profit load, that’s 15% of whatever the total spend is. If a hospital charges $10,000 for a surgery, and the insurer’s margin is 15%, they make $1,500 on that case to cover admin and profit. If the hospital charges $30,000 for the same surgery, and the insurer still gets 15%, that’s $4,500. The insurer’s percentage margin is the same, but in absolute dollars, they just made three times as much. Of course, higher claims also mean higher premiums to employers in the long run – but the insurer passes that along. In a fully insured plan, the employer pays the premium; in a self-funded plan, high claims feed into next year’s stop-loss premiums or ASO fees. Either way, the carrier isn’t losing sleep as long as they can justify the premium increase.

There’s a built-in incentive for carriers to let costs rise. They aren’t motivated to negotiate hospital prices down to Medicare levels – if they did, their slice of the pie (15-20%) would be a smaller pie. Relying on your carrier to reduce costs is like “asking a bartender to guard your sobriety.” The carrier likes it when you drink more – or in this case, when the healthcare system charges more – because their cut increases in absolute terms.

And this isn’t just cynical speculation; it’s been observed in behavior. Studies have noted that after the MLR rules took effect, insurers, in some cases, relaxed their cost-containment efforts. For example, an analysis in The American Journal of Managed Care found that insurers may respond to the MLR requirements by pulling back on aggressive tactics to reduce claims costs – doing less utilization management, being less aggressive in provider price negotiations – since they know they have to spend a certain proportion on claims (Medical Loss Ratio’s Role in the Large Group Insurer Market). In other words, if you have to hit 85% medical spending anyway, why fight to keep hospital prices low? There’s little reward for coming in under the limit. This dynamic helps explain why, despite consolidation on the insurance side too, we haven’t seen insurers use their power to force hospital prices down in line with Medicare. Many are content to pay 250% or 300% of Medicare as long as they can pass the bill to employers and still take their cut (Medical Loss Ratio’s Role in the Large Group Insurer Market).

The Self-Funded Risk Shift

There’s a secondary reason for an insurer’s apathy, at best, toward ever-escalating hospital contracts. As noted earlier, according to RAND, the commercial market pays 254% of Medicare for hospital treatment. But that is an average of pricing across all procedures. It is not weighted toward the kinds of procedures and care that a hospital truly wants to give. Whether their specialty is cardiac, trauma, or orthopedic surgeries, hospitals will regularly specialize in a type of care they want to foster. It is the care they’ve worked hardest at, that they’re most known for, and where they’ve ensured the best reimbursement terms they can garner from the carrier community.

Those averages, by themselves, mean almost nothing. The true cost lies in volume-weighted reimbursement.

One $800,000 open heart surgery (at 1200% of Medicare) gets buried under 7,000 dermatology visits reimbursed at 110% of Medicare. So, when the carrier says, "Hey, our average is 254%," it's a statistical smokescreen. The volume flows through the overpriced codes.

Worse, self-funded employers are the ones footing the bill. Carriers happily concede insane commercial reimbursements to hospitals in exchange for more favorable Medicare Advantage terms. After all, carriers don’t carry the risk—the employers do in self-funded plans. And more than 60% of covered people in the workplace are actually on a self-funded plan.

Taken together, whether you're looking at the self-funded or fully insured market, there is a glaring lack of incentive for carriers to keep provider reimbursements in check. On one hand, they’re risking nothing for self-funded clients and can even let those hospital contracts balloon in exchange for leverage in other lines of business. On the other, the ACA's MLR rules make inflated claim costs a means of boosting top-line revenue. If you ever wondered why your carrier isn't hammering the hospitals during negotiation, it’s because they don't benefit from lower costs. They benefit from higher ones.

What does this mean for you as an employer or plan sponsor? It means the deck is stacked against cost control in the traditional carrier model. The carrier isn’t strongly motivated to go to war with the hospital over prices – in fact, hospitals are often their partners in narrow networks, and higher allowed charges can benefit them both (hospitals get more revenue, insurers keep their percentage). This leaves employers in a vulnerable spot, assuming their carrier’s negotiating might is keeping costs in check when in reality it’s often not. Network discounts off inflated chargemaster prices are a shell game – a 50% discount sounds great until you realize the charge was marked up 800%.

The Bottom Line for Employers and Fiduciaries

If you, as an employer or benefits fiduciary, are comfortable paying 300% of Medicare rates for hospital services, you’re free to do so – but you should at least be honest with yourself about why. The data doesn’t support the notion that those exorbitant prices are necessary to subsidize public shortfalls or to keep hospitals solvent. Not even close. We’ve been told a convenient story that justifies the status quo, but mounting evidence and real-world examples have exposed that story as largely a myth.

For employers concerned about their healthcare spend (and the wages and business investments being crowded out by that spend), it’s time to rethink the payment model. The responsible, fiduciary path forward is to move toward a Reference-Based Pricing model grounded in transparency and fairness – something like the 125% of Medicare (or 120% of cost) approach discussed above. In practical terms, that means instead of blindly accepting a carrier network contract that pays whatever a hospital demands, you set a reasonable reference point tied to an external benchmark. Medicare gives us that benchmark. Paying roughly 125% of Medicare rates – which by the way is more than enough to allow an efficient hospital a fair margin – would slash employers’ costs dramatically while still paying hospitals well above their costs for care.

Such an approach aligns with actual provider costs, provides a decent profit margin for hospitals, and reins in the outrageous inflation that has characterized hospital pricing in the private sector. This is not about punishing hospitals; it’s about ending the blank-check era. Hospitals have done just fine under the current rules – many have built gleaming towers and amassed substantial reserves. It’s the employers and working families who’ve paid the price, in the form of stagnant wages and higher premiums, all to feed a system that has very little accountability on prices.

Reference-Based Pricing isn’t just a clever cost-saving strategy. It’s a fiduciary imperative. If you are responsible for managing a health plan, you have a duty to ensure that the plan’s assets (in this case, your premium dollars) are used prudently and for the exclusive benefit of plan participants. Continuously overpaying hospitals at 250-300% of Medicare, when there are viable alternatives, is hard to square with that duty. On the other hand, implementing RBP – with the necessary member protections and balance-billing safeguards – is a concrete step toward exercising true diligence over healthcare spending.

Employers and plan trustees nationwide should take a hard look at the numbers and ask themselves why they’re paying the equivalent of the “list price” without question. It’s akin to paying the full sticker price for a car without even peeking at the dealer invoice. The tools, data, and models now exist to do better. Some pioneering employers have already successfully implemented reference-based pricing and demonstrated substantial savings, often while steering more money into employee wages or other benefits.

In the end, the message to those still chasing ever-elusive “network discounts” off bloated hospital charges is simple: Stop paying the tip without ever checking the bill. The hospitals have named their price, and it’s been a doozy. It’s time for employers to call the bluff, insist on fair, transparent pricing tied to reality, and reclaim control over healthcare costs. Your employees’ livelihoods – and your company’s financial health – depend on it.

Employers, plan fiduciaries, and benefits professionals – step up. Challenge the old narratives. Scrutinize your payment model. Ask your vendors the hard questions about why you are paying what you pay. And strongly consider strategies like Reference-Based Pricing that put you back in the driver’s seat. The healthcare cost shift myth has had its day; now it’s time for a cost lift – lifting the lid on prices and lifting the burden off our businesses and workers. The solutions are there. We just need the will to use them.

Thank you! Thank you! I’ve been dealing with the magical money maze of Medicare for 5 years now. Mystery pricing and minimal accountability confuses everyone and sends many into the horribly named “Medicare Advantage” plans.